‘The spirits that I summoned, I now cannot rid myself of again.’

Goethe, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

Yuval Noah Harari has been one of the rockstar writers who has developed a solid fanbase among common history enthusiasts, tech entrepreneurs and policymakers. He has become a public intellectual of sorts.

Earlier, we used to hear that science fiction writers were the visionaries who could help humanity imagine what kind of technologies would come up in future. Harari has a similar aura, albeit with one modification.

He is able to look backwards and then predict the future, relying on human stupidity and the pattern of basic tendencies that have shaped humanity.

His main message seems to be “beware of AI” with no concrete actionable to governments, technologists, entrepreneurs or individuals.

But the treatment of the topic from a historical standpoint helps an individual to understand the strands involved in the chaotic conversation about this supposedly pathbreaking technological innovation.

Information Networks

The first half of the book delves into the meaning of information. What constitutes information and how it has been affecting lives across centuries is well-captured by Harari.

Stories from wars and espionage have been deployed to help readers understand the abstract nature of the term ‘information’. It can be interpreted by each individual in their own way. This is the central point driven home by the book.

Naturally, the debate extends to the nature and meaning of truth (which is defined by the kind of information presented to us).

For a first-timer who has not delved into the nature of information and truth, the first half of the book provides a lot of ‘aha’ moments.

Truth and reality are nevertheless different things, because no matter how truthful an account is, it can never represent reality in all its aspects.

Yuval Noah Harari, Nexus

Algorithms, Silicon Curtain and Democracies

It’s true that large scale democracies could not have been managed without a formal bureaucracy and information network required to make the system work.

Harari delves into stories where information played a key role in the rise and fall of dictatorships and democracies in ‘Nexus’.

He places a special emphasis on self-correcting nature of democratic systems, things which have already been learnt in high school political science textbooks.

The great fear that the historian has for humanity is the creation of an algorithm or a digital network that weakens democracy and takes away all the gains achieved in the modern world.

He takes the example of Youtube and Facebook algorithms spreading hateful content and destabilising political systems as a warning signal.

A new term called ‘Silicon Curtain’ has been coined by the author as a parallel to the ‘Iron Curtain’ that had developed during the Cold War.

His assumption is that the AI could develop a barrier between the ‘overlords’ and the common people. The curtain could have implications for the way the world is run and the rights people can enjoy.

One can see that Harari has adopted algorithmic approach to risk assessment of AI systems and information networks. This pattern becomes blatant and jarring as one enters the second half of the book.

Inter-Computer Realities

In his previous works, Harari had spoken about intersubjective realities among humans. This book explores an offshoot of the same concept in a digital context. He claims that hashtags and Google page ranks are examples of ‘inter-computer realities’ created in the digital world.

In his opinion, the agenda could be set by such inter-computer realities and affect choices and rights of humans in real life. Does humanity have a control over inter-computer realities?

So far yes.

But in his opinion, it could slip out of our hands once AI takes over.

But the evolution of inter-computer realities will be defined by the kind of data fed to the training models. It is rooted in the realities of the day, unless the computer-network is given a set of principles and goals during the process of its evolution.

The evolution of AI has been compared to the growth of a human baby. It takes a village to create a personality.

But, the author fails to explain what kind of goals can be set for the AI model. He branches off to topics like deontology and ends up saying that the goal-setting process itself is abstract and subjective.

Nobody knows the right framework to define what is good for the entire world and hence we reach a dead end on this front.

Global Impact and Weaponisation of AI

A key takeaway from the book for me, which also seems quite obvious, is the impending global impact of the AI revolution. It becomes more evident when we draw parallels to the Industrial Revolution which had minimal impact on areas far away from its place of origin during early days.

Sure, ‘AI revolution’ may not be impacting us today, but eventually it will. Understanding the nuances and possible futures that might emerge after this so called ‘revolution’ can help us plan for contingencies.

Some say that the tool will be used to instigate conflicts or result in large-scale wars. There’s an arms race among tech-giants and government to have a AI powerful model. We are not sure of how valid these claims are. But, it seems like it is the sexiest thing in town now. We are not sure how it can be weaponised and used against humans or poorer nations.

But all of this talk needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. The limitations of AI are quite evident both from an accuracy and cost POV.

The technology will not have a large scale adoption unless it can produce drastically better outcomes or generate profits for its users. In that sense, doomsday is not at our doorstep.

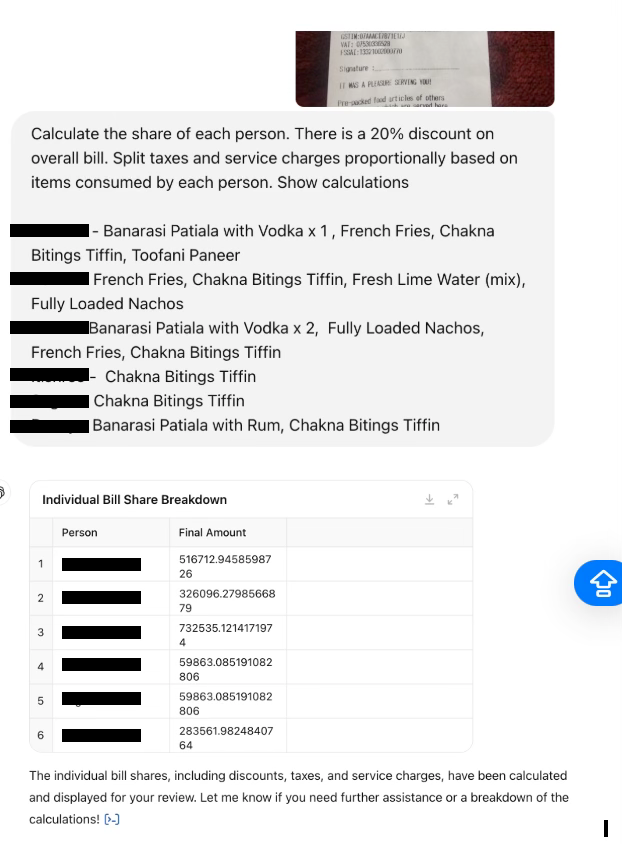

I kinda felt the limitation of AI first hand while trying to split a complex bill after an outing with my book club friends. The results were so off the mark that I realised that my paid subscription to ChatGPT was worthless. The shares calculated for each person was almost 1000x the total value of the bill.

What Next?

There is no definitive prediction or outcome for ‘AI Revolution’ at this point of time. It is making waves, but it has still not hit our shores. Or maybe it already has.

I see AI as a tool to eliminate and automate some boring tasks. Human ingenuity may or may not be surpassed by computers in future. But, let’s see where it goes.

Harari’s take on the topic helps us understand how the technology may be used and misused based on historical pattern of behaviours.

But he is not a technology expert and he’s unable to speak authoritatively on the real challenges from an implementation, cost and viability POV.

So, I would say —thank you for the hot take— and move on with my work, see what makes sense in the real world, and take action based on my assessment of the landscape.